The Dying State Organism

Von Timo Braun – veröffentlicht durch den Ethical Council of Humanity

How Guilt, Money and Overregulation Reveal the Decline of Modern States

A systemic analysis of Germany, Europe and the global order

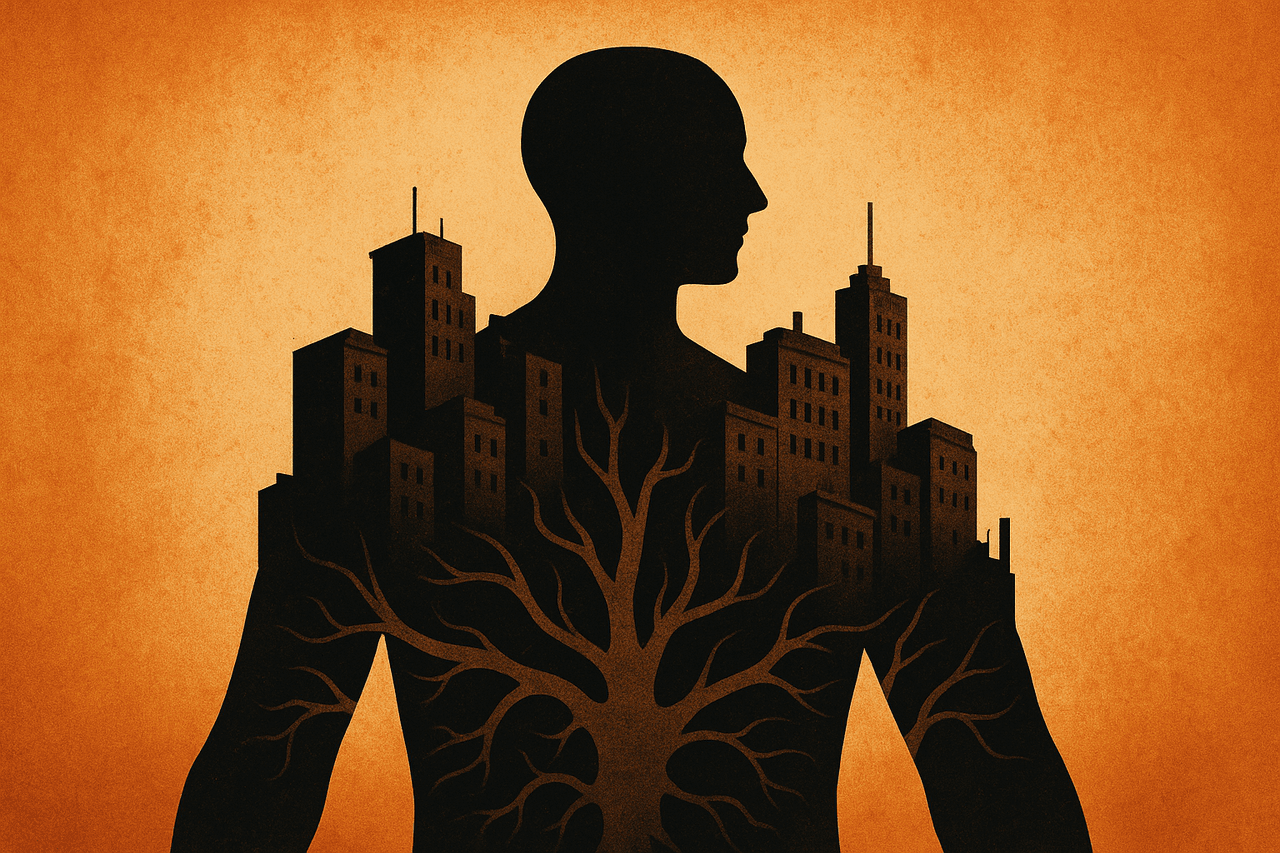

1. Introduction: States as Complex Organisms

Modern states functionally behave like complex organisms: they consist of networks of energy flows, communication, feedback mechanisms and self-regulating subsystems. Niklas Luhmann describes social systems explicitly as autopoietic, self-referential and structurally coupled—similar to biological organisms that reproduce their operations and metabolism internally.1

Historical complexity research further shows that societies tend to enter a pattern of rising complexity, expanding regulation, declining problem-solving capacity and increasing energetic strain in late developmental phases. This pattern was fundamentally described by Joseph Tainter in The Collapse of Complex Societies.2

Against this background, it is analytically legitimate to compare contemporary state structures—such as Germany or the EU—not metaphorically, but structurally to biological organisms.

2. Historical Patterns of Decline: Rome, the Ottoman Empire, the Soviet Union

2.1 Late Roman Empire: Tax Burden, Price Controls, Bureaucratic Expansion

Under Diocletian, the late Roman Empire saw massive price controls, tax increases, rapid administrative expansion, and deep interventions into professional and social life. The Edictum de Pretiis Rerum Venalium (301 CE) fixed maximum prices and wages and punished violations severely.3 Research shows that these measures generated black markets, weakened the economy and eroded public trust.4

2.2 Ottoman Empire in the 19th Century: Debt Trap and Creditor Oversight

In the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire responded to military, fiscal and geopolitical crises with extensive centralisation, escalating borrowing and swelling bureaucracy. Şevket Pamuk documents how exploding public debt led to the establishment of the Ottoman Public Debt Administration in 1881—an international creditor authority controlling major state revenues directly.5 This mechanism is now seen as a classic case of an overstretched imperial system entering decline.6

2.3 Late Soviet Union: Moralised Overregulation

In the late Soviet Union, economic problems were increasingly interpreted as moral failure. Elena Kochetkova documents how “people’s control”, reporting obligations and moral campaigns created excessive regulation while real performance declined.7 Again we see the pattern of an overreactive immune system inside a degenerating organism.

3. Theoretical Framework: Complexity, Diminishing Returns and Systemic Collapse

Tainter shows that complex societies respond to challenges with additional complexity: new institutions, new regulations, intensified oversight. Initially stabilising, this later produces diminishing marginal returns—the cost of complexity exceeds its benefits, and the organism becomes fragile.2

Modern systems-science models show that contemporary democracies risk entering a phase of structural degeneration driven by hypercomplexity, resource stress and institutional self-insulation.8

Luhmann helps explain why: Subsystems such as politics, law or administration reproduce their own functional logic during crises instead of simplifying—analogous to biological inflammatory processes.1

4. Application to Germany: The Degenerative Pattern

All classic signatures of decline are visible in Germany today:

4.1 Energy Blockage (Financial Flow)

- record-level taxes and levies

- state spending at historic highs

- stagnating productivity and growth

4.2 Overregulation

Regulatory waves in energy, construction, labour, supply chains and compliance increase transaction costs—precisely as in the late Roman model.3

4.3 Guilt Logic as a Governance Tool

Guilt is no longer episodic but structural—legally, fiscally and morally—from households to the national budget.

4.4 Administration as Overreactive Immune System

As in the late Soviet Union, the apparatus for control, audit and documentation grows faster than its capacity to solve problems.7

This resembles a chronic inflammatory condition: The system consumes energy trying to regulate itself, weakening the whole organism.

5. Europe: Overcompensation Through Control

The same pattern can be seen at EU level:

- extremely high regulatory density

- centralised decision-making

- increasing tendencies toward surveillance and pre-emptive control

Political science analyses interpret this as structural insecurity and overload—similar to the final phases of historical large systems.8

6. Global Pattern: The Earth-Organism Under Strain

Complexity research, climate science, governance studies and sociological meta-analyses confirm: The global order is entering a loop of overload, marked by:

- institutional fatigue

- expanding regulation

- declining problem-solving capacity

- rising inequality

- resource stress

These dynamics mirror the mechanisms of historical systemic collapses.8

7. Conclusion: The Organism Is Real, Not Metaphorical

The parallels between biological organisms and political systems are structural, not poetic:

- guilt = toxic signalling molecule

- money = energy flow

- administration = immune system

- bureaucracy = inflammation

- overregulation = autoimmune response

- systemic failure = organ failure

Germany, Europe and much of the world exhibit measurable end-stage patterns known from history, systems theory and complexity science.

The alternative to collapse is the biological alternative:

Relief, inflammation reduction, dismantling toxic guilt structures, and restoring free energy flows.

This not only explains decline—it makes transformation scientifically feasible.

Appendix: Systemic Euthanasia – When a Macro-Organism Reaches the End of Its Cycle

In medicine, euthanasia does not mean ending life, but preventing unnecessary suffering caused by artificial life extension, allowing a natural transition.

Applied to large state systems, the principle is precise:

A state is not a political construct. It is a macro-organism composed of dozens of interconnected organs.

These include:

- legal system (immune logic)

- administration (metabolism and distribution)

- financial system (energy allocation)

- social system (regeneration and reintegration)

- security system (protective mechanisms)

- media (signalling and hormonal system)

- infrastructure (circulation)

- economy (energy production)

- EU superstructure (supra-regulatory layer)

In end-phase conditions, such organisms display:

- autoimmune reactions (state vs. citizen)

- inflammatory processes (bureaucracy, control, overregulation)

- energy stagnation (financial blockages)

- organ failure (justice system, administration, infrastructure)

- overcompensation (symbolic politics, moralising narratives, sanctions)

- cellular stress (population exhaustion)

Artificial stabilisation intensifies decline:

- more rules

- more oversight

- larger apparatus

- higher costs

This mirrors the medical mistake of force-ventilating or sedating a dying body while its metabolism no longer responds.

Systemic euthanasia therefore means:

- relief instead of retention

- shutting down toxic functions

- ending artificial complexity

- allowing the transition into a new order

It is not destructive; it is the only gentle, life-serving path for transforming large organisms.

- No organ is “killed.”

- No system is “destroyed.”

- The macro-organism stops fighting itself, allowing a new functional state to emerge.

Just as every cell and living being completes its cycle, so does every state:

Not through collapse when it lets go, but through renewal when it stops clinging to artificial survival.

Footnotes

Niklas Luhmann, Social Systems, Suhrkamp, 1984; The Society of Society, Suhrkamp, 1997. ↩ ↩

Joseph A. Tainter, The Collapse of Complex Societies, Cambridge University Press, 1988. ↩ ↩

Edictum de Pretiis Rerum Venalium (Diocletian’s Price Edict), 301 CE; see Peter Temin, “Price Controls in the Roman Empire,” Journal of Economic History. ↩ ↩

Michael Rostovtzeff, The Social and Economic History of the Roman Empire, Oxford University Press. ↩

Şevket Pamuk, The Ottoman Empire and European Capitalism, 1820–1913, Cambridge University Press. ↩

Christine Philliou, The Ottoman Empire and Its Discontents, University of California Press. ↩

Elena Kochetkova, “People’s Control and the Morality Quest of the Late Soviet Union,” Journal of Social History. ↩ ↩

Geoffrey West, Scale; Peter Turchin, End Times; various complexity-science models, incl. S. Schunck et al. ↩ ↩ ↩